|

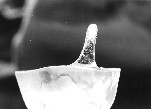

Got Spikes

on Your Ice Cubes? |

|

you are not alone ...

Why do ice cubes grow spikes?

The short explanation is this: as the ice freezes fast under supercooled

conditions, the surface can get covered except for a small hole. Water

expands when it freezes. As freezing continues, the expanding ice under

the surface forces the remaining water up through the hole and it

freezes around the edge forming a hollow spike. Eventually, the whole

thing freezes and the spike is left.

A slightly longer explanation: the form of the ice crystals depends on the cooling rate and hence on the degree of supercooling. Large supercooling favors sheets which rapidly cover the surface, with some sheets hanging down into the water like curtains. These crystallites tend to join at 60 degrees and leave triangular holes in the surface. Hence, spikes often have a triangular base. The sides of the spike are sometimes a continuation of pre-existing subsurface crystallites, and can extend from the surface at steep angles.

Pictures of spikes on ice cubes:

With very cold (-10C to -20C) freezer conditions, spikes will often form during the rapid freezing of ordinary ice cubes. In a frost-free freezer, the kind that most people have, initially sharp spikes will take on a rounded appearance as they slowly sublime away.

Movies of growing spikes:

- A quicktime movie of a spike growing, made by Michael T. Rosenstein. Note the clock showing the speed of the process. You can just see the final bit of water freezing in the interior of the spike.

- Compressed avi movie of a controlled ice spike growth experiment. The frame rate is about 50X normal time. The air

temperature was -11.5C and the grid

squares are 1 mm. The colours that appear on the ice surface toward the

end of the video are potassium permanganate crystals sprinkled onto the ice. It looks as if there is evidence of a liquid layer on the surface, suggesting (though not conclusively) that there is some overflow at the spike orifice near the end of its growth. Movie made in the ice lab of Edward Lozowski at the University of Alberta. Movie by Lesley Hill, Russ Sampson and Edward Lozowski, with technical help by Kenny Lozowski.

- Two videos of a freezer experiment to grow spikes: [video 1][video 2] provided by Christian Krause. Full credits: Grundpraktikum Physik, Heinrich Heine Universität Düsseldorf Vadim Abramov, Christian Keller, Christian Krause, Masdak Nadem Boueni,

Serkan Özdemir, Kapilan Paramasivam.

Spikes in the great outdoors:

Spikes are occasionally seen in a natural setting. Since rapid freezing under supercooling is required, they are usually the result of someone leaving a relatively small volume of room temperature water outdoors overnight.

- An image of a spectacular spike seen in Anne Davies' backyard birdbath in Comox British Columbia, January 11, 2003. The grey object is a rock which holds the tub on top of a post. Photo by Marilyn McCourt.

- A side view of the birdbath spike.

- A closer view of the birdbath spike.

- A spike in the birdbath belonging to Edward and Rosemary Williams, in Malvern, Worcs, UK. Night temperature was -6C.

- Closer view of Malvern spike.

- Ice Vases that appeared in Sarah Longrigg's backyard in Scotland.

- An account of a 1963 walk across frozen Lake Erie, during which natural ice spikes "the size of telephone poles" were observed. By Harold Kirk, from the Harbor Creek Historical Society Newsletter. Thanks to Beth Simmons.

- Four images [1][2][3][4] of icespikes taken on January 2, 2010, about 15 miles east of Richmond, Virginia USA, by Anne Morrow Donley. The first two are of the dog/cat water bowl; the other two are "down near the chicken yard in buckets that catch the runoff of rainwater from the chicken house".

- Ice spikes on a frozen stream downstream from a weir, Des Lacs River near Foxholm, North Dakota, Winter 2010-2011.

- Seven images of an amazing ice spike in the form of an inverted pyramid: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7], taken by Steven Hilsdon, Roy, Washington, USA. The temperature was -1.7C. You can clearly see the crystals in the surface of the rest of the ice.

Links to other pages about spikes:

References:

- H. E. Dorsey, "Peculiar Ice Formation", The Physical Review (series I), vol. 18, p. 162 (1921). [available here from PROLA] Describes and shows images of a spike observed on the night of December 15, 1916.

- D. C. Blanchard, Journal of Meteorology, vol. 8, p. 268 (1951). Describes spicules on sleet pellets.

- B. J. Mason and J. Maybank, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, vol. 86, p. 176 (1960). Describes spicules on and splintering of sleet pellets.

- J. Hallet, Journal of Glaciology, vol. 3, p. 698 (1960). Describes the crystalography of the spikes in detail.

- Thomas Wäscher, "Generation of slanted gas-filled icicles,"

Journal of Crystal Growth, vol. 110, p. 942-946 (1991).

- Helene F. Perry, The Physics Teacher, vol. 31, p. 112 (1993), and followup letters in vol. 31, p. 264 (1993). The "last word on ice spikes", The Physics Teacher, vol. 33, p. 148 (1995).

- G. Abrusci, American Journal of Physics, vol. 65, p. 941 (1997). Describes an outdoor spike sighted in January 1997.

- C. A. Knight, American Journal of Physics, vol. 66, p. 1041 (1998). Response to the previous reference.

Go to the Nonlinear Physics Group

home page

The Experimental Nonlinear Physics Group, Dept. of Physics, University of

Toronto,

60 St. George St. Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S 1A7. Phone (416) 978 - 6810