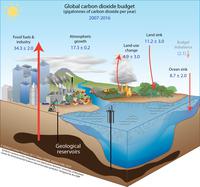

Climate change is driven

primarily by anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases, chief among them

carbon dioxide and methane. Two fundamental challenges in carbon cycle science

are (1) to quantify human emissions of greenhouse gases at scales ranging from

the individual to the globe and from hours to decades, and (2) to anticipate

how the “natural” (e.g. oceans, land) components of the carbon cycle will act

to mitigate or to amplify the impact of human emissions. Spatiotemporal

variability in observations of atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases

can be used to tackle both challenges, because the atmosphere preserves

signatures of emissions and uptake (a.k.a. fluxes) of greenhouse gases at the

Earth’s surface. The process is analogous to being handed a creamy cup of

coffee and being asked to infer not only when and where the cream was

originally added to the cup, but ideally also who poured it in and why. This

talk will give an overview of the use of inverse problems in carbon cycle

science, focusing on the question of whether we can use atmospheric

observations not only to quantify and locate fluxes but also to directly probe

the underlying biogeochemical processes and their sensitivity to climate

change.

Climate change is driven

primarily by anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases, chief among them

carbon dioxide and methane. Two fundamental challenges in carbon cycle science

are (1) to quantify human emissions of greenhouse gases at scales ranging from

the individual to the globe and from hours to decades, and (2) to anticipate

how the “natural” (e.g. oceans, land) components of the carbon cycle will act

to mitigate or to amplify the impact of human emissions. Spatiotemporal

variability in observations of atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases

can be used to tackle both challenges, because the atmosphere preserves

signatures of emissions and uptake (a.k.a. fluxes) of greenhouse gases at the

Earth’s surface. The process is analogous to being handed a creamy cup of

coffee and being asked to infer not only when and where the cream was

originally added to the cup, but ideally also who poured it in and why. This

talk will give an overview of the use of inverse problems in carbon cycle

science, focusing on the question of whether we can use atmospheric

observations not only to quantify and locate fluxes but also to directly probe

the underlying biogeochemical processes and their sensitivity to climate

change.