By Margaret Munro, Postmedia News

High above the Arctic, winds swirling around the pole in the winter darkness are isolating an air mass that will grow colder and colder over the coming weeks.

It will create what James Drummond, an atmospheric physicist at Dalhousie University, likes to describe as a "chemical cauldron" around the pole — one that can do nasty things to the Earth's protective ozone layer.

Last year, the cauldron chewed an unprecedented hole in the Arctic ozone. It is anyone's guess what will unfold this winter.

The 2011 hole is thought to have been a rare one-off occurrence. And there will be plenty of concern if there is a repeat in 2012.

"If we were to have ozone holes on a regular basis, that would imply that we don't understand what is going on," says Drummond, one of Canada's leading atmospheric scientists. "And when you don't understand, then you start worrying."

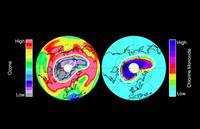

The 2011 hole formed in February and March, and eventually grew to two million square kilometres — about twice the size of Ontario. It swung across northern Canada, northern Europe, then dipped down to Central Russia to Northern Asia, prompting scientists to issue warnings about excess ultraviolet radiation.

The stratospheric ozone layer, 15 to 35 kilometres above the ground, protects the planet from the sun's harmful ultraviolet rays, which can cause skin cancer and damage crops.

Canadian researchers had front-row seats as the hole formed. They were working at a science outpost, the Polar Environment Atmospheric Research Laboratory on Ellesmere Island, 1,500 kilometres above the Arctic Circle and about as far north as you can get and still be on land.

In the darkness that lasts all day at the lab in the winter months, the researchers were probing the upper atmosphere as part of a long-running monitoring program.

"We were sitting there inside the vortex," says Kimberly Strong, an atmospheric physicist at the University of Toronto, referring to the polar cyclone that settled over the Arctic last winter.

It made for some particularly frigid working conditions for her graduate students, but was the ideal spot to watch the ozone hole.

Using lasers, spectrometers and data recorders, which on good days were carried 30 kilometres up into the atmosphere by giant balloons, they amassed data that has been invaluable in understanding why the hole formed.

"All the bits and pieces of the puzzle are coming together," says Strong, whose team presented its data at the recent American Geophysical Union meeting.

She says it appears the ozone hole was a one-off event tied to last year's usual vortex, which saw temperature in the upper atmosphere plunge below -78 C.

"Things just came together," Strong says. "The vortex was very stable; it was very cold. Conditions were just right."

Temperatures were so cold that polar stratospheric clouds of nitric acid and water started forming at the same altitude as the ozone layer.

Then, when the sunlight returned with the polar sunrise in late February, it triggered "photochemistry" that chewed up the ozone, the scientists say.

They watched in awe as almost 40 per cent of the ozone disappeared, the biggest depletion of ozone ever recorded in the Arctic.

There are plenty of lingering questions, says Drummond, who likens it to a murder scene.

"It's like having the body on the floor," he says. "You can say: 'Yes, there's been a crime.' But what led up to it?"

The researchers say ozone-destroying chlorine compounds in the atmosphere played a role. The chemicals have been banned internationally under the Montreal Protocol, but are so "long lived" they are expected to linger in the atmosphere for decades.

Continued here http://www.canada.com/technology/Arctic+mystery+What+killed+ozone+will+strike+again/5936132/story.html